Medieval Guide Dogs

This online exhibit/page is designed to introduce and make accessible some of the findings from my project on medieval guide dogs, which was funded by the Dutch Research Council’s Open Competition XS grant. The goal of this project was to identify and collect medieval artistic and textual representations of guide dogs from four regions (The Netherlands, Belgium, the UK, and France). The project focused on representations created between 1100 and 1500, although representations created outside of this date range were also considered.

Here is an example, from a fourteenth-century collection of Alexander romances produced in Flanders:

Note: Information about how the guide dogs were identified for this project is available here.

This exhibit is designed to be accessible to everyone; academic analysis of the representations that appear here (and others) appears in my forthcoming book on the topic.

All images here are creative commons licensed (Licence Creative Commons Attribution – Pas d’Utilisation Commerciale 3.0 non transposé), unless otherwise indicated. All come accompanied by image descriptions (for use with, e.g., screen readers). Other images that were identified for this project, including those that are not creative commons license, have not been included on this page but are discussed in my forthcoming book.

If you would like to discuss one of the examples that you learned about on this page in an academic work, here is the citation information for this page: Milne, K.A. “Medieval Guide Dogs [Funded by NWO’s Open Competition Grant], 2025. wwww.kristamilne.com/guidedogs. Accessed [replace with date].

It was once believed that guide dogs are a modern (i.e. post-1400) phenomenon, but they have a long history.

This image of a guide dog, for example comes from the medieval Bible jaromĕřska (Prague, Mus. Nat. Bibl. XII.A.10, f. 69v). The image was produced in the late thirteenth century in Northern France.

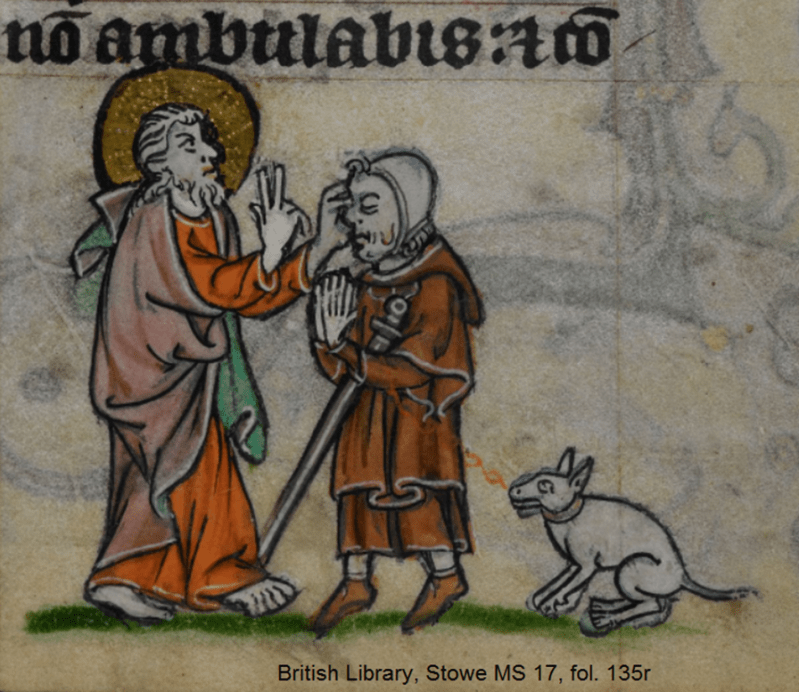

Here is another example, which is taken from the fourteenth century Maastricht Hours. The example illustrates the episode of Christ giving sight to a blind man. In the image, the blind man receives sight from Christ while his small white dog watches the scene unfold.

Representations such as these ones reveal new information about medieval approaches to guide dogs and, in so doing, strengthen our understanding of the roots of modern-day attitudes toward guide dogs.

Guide Dogs in Medieval Romance Manuscripts

While the examples discussed appear in religious manuscripts, some of the representations of guide dogs collected for this project appear in manuscripts of medieval romances. This example appears in a collection of Arthurian romances produced toward the end of the thirteenth century, likely in Flanders. The scene illustrates an episode that appears in the accompanying romance in which a mysterious blind messenger (later revealed to be Merlin) appears in Arthur’s hall playing a harp and accompanied by a small guide dog.

Here is another example of a guide dog produced around the same time that illustrates the same narrative. In both illustrations, the guide dog accompanying the messenger is small and white.

A Variety of Types

While the dog in the image above is relatively small, medieval representations of guide dogs depict a wide range of different types and sizes, including this large brown dog with pointed ears:

The example above comes from a copy of the Smithfield Decretals that is now in the British Library collection (it’s the same example I mentioned in a 2017 post that was designed to draw attention to the presence of guide dogs in medieval manuscripts).

Guide Dogs with Bowls

In many of the examples identified for this project, guide dogs are depicted alongside people wearing tattered clothes or otherwise depicted as economically disadvantaged (the reasons for this are discussed in my book). The example here is described as a beggar accompanied by a dog in Lilian M. C. Randall’s Images in the Margins of Gothic Manuscripts (1966).

This dog, like many of the ones discussed here, holds a bowl in his mouth for collecting alms (or charitable donations). In medieval Europe, many blind people faced significant financial difficulties (as discussed in this blog post from 2018).

The image is from the collection of the The Metropolitan Museum of Art. CC0 licensed.

Where were representations of guide dogs produced?

The example above was produced in Flanders. Several of the examples identified for this project were also produced in this region.

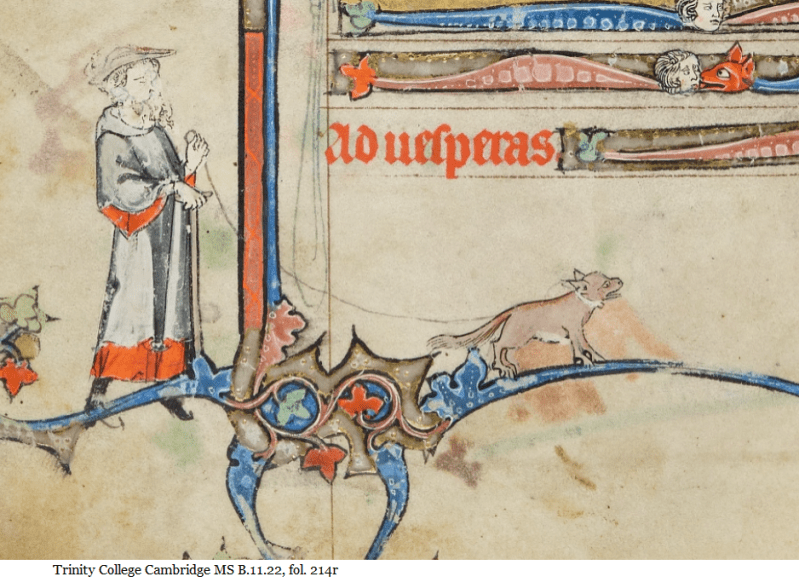

Here is another example, from a Book of Hours produced in Flanders c. 1300:

Northern France is also well represented among representations identified for the project. Why these regions? The reasons are explored in my book, which is forthcoming later in 2025 and which presents the analysis of the images presented here and of other representations identified for this project. As this book shows, exploring representations of medieval guide dogs is valuable, because it provides insight into medieval cultural history, and into the roots of modern day attitudes and approaches toward guide dogs.