Were there guide dogs in medieval Europe? And what is the earliest picture of a guide dog? These questions are important for the history of disability and for our understanding of medieval culture.

It has been suggested that the earliest surviving illustration of a guide dog (in the sense of a dog providing mobility support to a person with impaired vision) from Western Europe dates to the late fifteenth century.[1] But there are actually several earlier depictions of guide dogs that survive in medieval manuscripts.

One of these is in a manuscript of the Decretals of Gregory IX produced in the South of France around the end of the thirteenth century (this is the same one I tweeted about awhile ago). The blind man wears patched clothing and seems to be a beggar:

In keeping with a growing (and important) interest in the history of disability, the goal of this post is to point to the variety of representations of guide dogs in medieval manuscripts, and to explore some of the roles of guide dogs in medieval Europe.

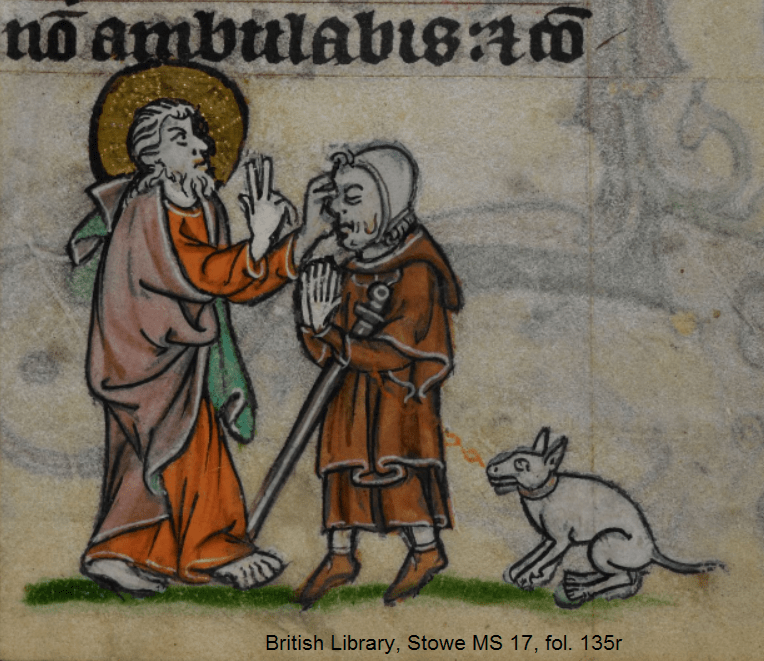

Our search for medieval guide dogs leads us to a Book of Hours (a popular type of medieval prayer book) produced slightly later, in the first quarter of the fourteenth century. Here, a blind man receives sight from Christ while his dog looks on:

It is striking that, among the manuscript illustrations of medieval guide dogs that have been identified, many are from such prayer books. A near-contemporary illustration of a blind man with a dog can be found in another Book of Hours, produced for a woman in Ghent (c.1315-25):[2]

Given their contexts within medieval prayer books, such images may have been intended as sites of ennobling reflection.

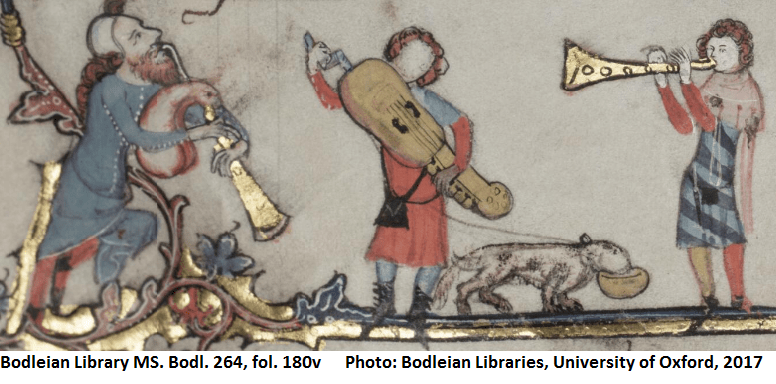

Guide dogs with bowls

Why is the charming pup in the image above carrying a bowl? This dog, like the one in this mid-fourteenth century manuscript, may be collecting alms for his owner, since blind people in medieval Europe often faced significant financial struggles.[3]

One of the major causes of blindness in medieval Europe was leprosy (now often known as Hansen’s disease). While cases of leprosy are relatively rare and largely treatable in present-day Europe, in the late medieval period they were much more common. Leprosy was associated with sin, and those who had it were often condemned to social exclusion and forced to live as beggars–a fate represented perhaps most famously in Robert Henryson’s Testament of Cresseid.[4]

Another depiction of a guide dog with a bowl, from the Hours of Mary of Burgundy (c. 1477)

The earliest depiction of a guide dog?

These examples prove that guide dogs and their owners captured the imagination of artists and writers long before the fifteenth century. But the history of representing guide dogs in art has been traced back even further. Indeed, the earliest depiction of a guide dog in Western Europe may be in a wall painting preserved from Pompeii in 79 CE.[5]

Did pre-modern people feel the same about guide dogs as we do now? It has been argued that guide dogs were considered unreliable in the medieval period. Irina Metlzer, in her groundbreaking Social History of Disability in the Middle Ages, gives two examples to show that guide dogs were thought unreliable; she notes that Bartholomaeus Anglicus’ De proprietatibus rerum (c. 1240) describes dogs as too easily distracted to lead the blind. And she writes that in Heinrich von Mügeln’s fourteenth-century De meide kranz, a ruler without reason is compared to a blind person led astray by a dog, child, or cane (“künk ane sin gelichet ist / dem blinden, den eins hundes list / muß leiten adr ein junges kint / ader ein stap, der selb ist blint”).[6]

But negativity about guide dogs was not in any way universal. Indeed, a teacher of rhetoric in twelfth-century Constantinople, Nikephoros Basilakes (c. 1115 to 1182), wrote an “Encomium” (or work of praise) about dogs, in which he describes the virtues of guide dogs:

“Why do I not mention the most unusual characteristic of all, that he leads the blind and becomes another eye for them, and that he leads them around everywhere to beg for bread at people’s doors, and then leads them back again to their lodging?”

According to Basilakes, guide dogs are actually better than people in this respect, “[f]or something humans do not even tolerate doing for each other is precisely what this irrational animal does for humans.”[7] For Basilakes, then, guide dogs could provide excellent support to the blind.

A long-standing tradition

Although the roles of guide dogs in pre-modern Europe have been downplayed or ignored, the evidence reveals that there was a long and fascinating history of representing guide dogs in medieval writing and art. Guide dogs feature in diverse medieval contexts and their presence in medieval prayer books suggests that their illustrators saw them as well suited to contexts of piety and devotion. And these representations, by offering us an important slice of medieval culture, can continue to enchant hundreds of years later.

Notes

1 For the suggestion that a 1465 woodcut contains the earliest illustration of a guide dog, see Gerald A. Fishman, “When Your Eyes Have a Wet Nose: The Evolution of the Use of Guide Dogs and Establishing the Seeing Eye,” Survey of Ophthalmology 48, no. 4 (2003): 452-58. [Back]

2 The image is described by Mosche Barasch in Blindness: The History of a Mental Image in Western Thought (London: Routledge, 2001), 173, n. 7. [Back]

3 For a description of this image, and the suggestion that the dog’s bowl is for alms, see Lucia Reily’s “Músicos Cegos Ou Cegos Músicos: Representações De Compensação Sensorial Na História Da Arte,” Cadernos Cedes 28, no. 75 (2008): 245-66. [Back]

4 For a discussion of the representation of blindness and leprosy in medieval literature, see Tory Vandeventer Pearman’s “Refiguring Disability: Deviance, Punishment, and the Supernatural in Bisclavret, Sir Launfal, and the Testament of Cresseid,” in Women and Disability in Medieval Literature, ed. T. Pearman (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 96-111. The image is mentioned by Hannele Klemettilä in Animals and Hunters in the Late Middle Ages: Evidence from the BnF MS Fr. 616 of the Livre De Chasse by Gaston Febus (New York: Routledge, 2015), 111, no. 2. [Back]

5 For the claim that this fresco is the earliest representation of a guide dog, see Fishman, “When Your Eyes“, 452-458. [Back]

6 See Irina Metzler, A Social History of Disability in the Middle Ages: Cultural Considerations of Physical Impairment (New York, NY: Routledge, 2013), 178. The image is mentioned here. [Back]

7 Nikephoros Basilakes, “Encomium,” in The Rhetorical Exercises of Nikephoros Basilakes, ed. and trans. by Jeffrey Beneker and Craig A. Gibson (Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2016), 136-7. This passage is discussed by Craig A. Gibson in “In Praise of Dogs: An Encomium Theme from Classical Greece to Renaissance Itality,” in Our Dogs, Our Selves: Dogs in Medieval and Early Modern Art, Literature, and Society, ed. Laura D. Gelfand (Leiden: Brill, 2016): 19-40, at 28. [Back]